Ebola Vaccinations For Staff Exceed 8,000 in Africa

A crushing fear of the disease among many in his neighborhood in Mbandaka, the capital of Equateur province in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) hobbled the initial response to the country’s 11th Ebola outbreak.

Terrified of the rare but often fatal disease, many people in the DRC were wary and unreceptive of the response teams working to halt the virus, while lack of a clear understanding of Ebola prevention and treatment fuelled misconceptions.

“When people don’t have the right information, they are reluctant,” said Dr. Mory Keita, the World Health Organization (WHO) Ebola Incident Manager in Equateur province, in a press release. “In the community Ebola is seen as a grave and mortal danger. This causes fear and reticence.”

The Ebola virus disease is a viral hemorrhagic fever caused by ebolaviruses. These viruses, also known as Zaire ebolavirus, Sudan ebolavirus, and Bundibugyo ebolavirus, can cause severe hemorrhagic fever, says the WHO.

Community resistance was one of the major challenges the DRC government, the WHO, and other partners faced during the response. Working with youth leaders and local authorities helped facilitate acceptance and allow response teams to reach the affected communities. The youth leaders went door to door and persuaded reluctant people to seek treatment or get the Ebola vaccine which provides highly effective protection.

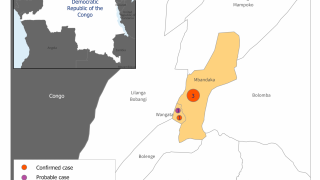

With affected communities spread across 13 of Equateur’s 18 health zones spanning a wide geographic area, access to many localities was difficult. In addition to the expansive distances, road travel remained limited in the densely forested region, with some remote areas only accessible by air or by boat.

Overcoming the logistical challenges also meant decentralizing the response and working closely with community health workers to set up response systems and make them effective at the local level.

Part of the strategy included a meticulous listing of contacts of an Ebola patient by community surveillance teams. This enabled emergency responders to rapidly circumvent the virus.

“We managed to contain every case within the area in which it was reported. This helped to limit the spread,” explains Dr. Jeremie Muhundo Vutenga, an epidemiologist and a member of the surveillance team in Mbandaka.

Once contact-tracing and surveillance were established within an area, vaccination teams moved in to break the chain of transmission. In Ingende locality, for instance, it took just one month to contain the disease from the time the first case was confirmed.

“In this Ebola outbreak, we were present even in unaffected areas. Expanding response activities in such areas helped detect new cases by locality,” Dr. Keita explains.

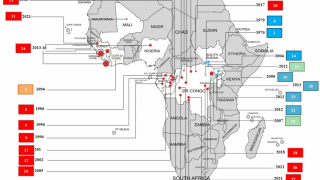

The response teams have built a lot of expertise in fighting Ebola, and they were able to devise strategies to counter the virus. The Equateur province experienced a 3-month Ebola outbreak which ended in June 2018. Investment in local health worker training during the earlier outbreak paid off.

Swift action by laboratory technicians trained during the 2018 response helped detect the first cases in the 2020 outbreak and enabled the government to respond quickly.

During this outbreak, more than 5,000 health workers were trained in infection prevention. Additional training is to be conducted over the next 3-months to strengthen health workers’ knowledge and skills for effective emergency response.

With over 8,000 health workers vaccinated against Ebola, no cases were reported among health workers during the outbreak, which was declared over on November 18, 2020.

There were a total of 119 confirmed cases, 11 probable, 55 deaths, and 75 people who recovered, reported the WHO.

Updated Ebola vaccine news can be found at this link.

Ebola vaccination news is published by Vax-Before-Travel.

Our Trust Standards: Medical Advisory Committee