Zika, Gone For Now, But Not Forgotten in 2019

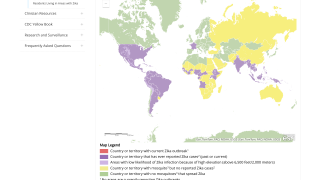

A new article in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) says ‘Zika's origins and effects are complicated, that outbreaks are still happening, and that we are ill-prepared for the next time Zika hits.’

‘We just don't know where or when. And when it comes, we're not fully prepared.’

In this NEJM editorial published on October 9, 2019, these researchers say ‘We're in a quiet phase with Zika, but it will strike again.’

Excerpts from this NEJM article, with a focus on Zika’s impact on children, are inserted below:

‘Since the Zika epidemic of 2015 and 2016 sickened thousands of people in the Americas, researchers have attempted to answer key questions about this harmful flavivirus.

The ability of the Zika virus (ZIKV) to cause congenital defects in fetuses and infants, as exemplified by the microcephaly epidemic in Brazil, is an unprecedented feature in a mosquito-borne viral infection.

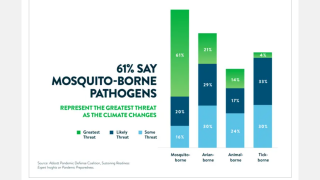

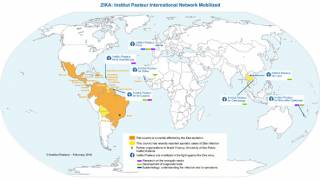

Mosquito-borne transmission is the primary mechanism for epidemic spread. A. aegypti is the major vector for horizontal transmission of ZIKV to humans.

A. albopictus, which has a greater distribution in temperate climates, is a competent vector but does not appear to play an important role.

Predictive models suggest that the geographic distribution of A. aegypti will continue to expand as a consequence of population growth and movement, urbanization, and climate change.

However, ZIKV can be transmitted to humans by non-vectorborne mechanisms, such as blood transfusion.

Moreover, Zika is unique among arboviruses in that it can be transmitted during sexual contact and can cause teratogenic outcomes as a consequence of maternal-fetal transmission.

In humans, male-to-female sexual transmission can occur whether the male partner with ZIKV infection is symptomatic or asymptomatic and has been observed more frequently than female-to-male and male-to-male transmission.

Although the effect of sexual transmission in areas in which the virus is endemic is difficult to assess, estimates are that 1 percent of ZIKV infections reported in Europe and the United States were acquired through sexual transmission.

Related Zika news

ZIKV RNA has been detected in semen, by reverse-transcriptase–polymerase-chain-reaction assay, up to 370 days after onset of illness, but the shedding of infective viral particles is rare after 30 days from the onset of illness.

Although alterations in semen and sperm quality have been observed in men with ZIKV infection, an adverse effect on male fertility has not been shown.

Maternal-fetal transmission of ZIKV may occur in all trimesters of pregnancy, whether infection in the mother is symptomatic or asymptomatic.

Vertical transmission has been estimated to occur in 26 percent of fetuses of ZIKV-infected mothers in French Guiana, a percentage similar to transmission percentages that have been observed for other congenital infections.

Related Zika news

Among fetuses that were exposed to ZIKV by vertical transmission, the fetal loss occurred in 14 percent and severe complications compatible with congenital Zika syndrome occurred in 21 percent.

In addition, 45 percent of the fetuses that were exposed to ZIKV by vertical transmission had no signs or symptoms of congenital Zika syndrome in the first week of life.

Although infective ZIKV particles have been detected in breast milk, a milk-borne transmission has not been confirmed as a mode of transmission.

At present, the WHO recommends that mothers with possible or confirmed ZIKV infection continue to breast-feed their infants.

As became evident early in the microcephaly epidemic, ZIKV causes a spectrum of fetal and birth defects that extends beyond microcephaly and is distinct from other congenital infections in that its pathologic manifestations are restricted primarily to the central nervous system.

Although these anomalies are seen in other congenital infections, they appear to be more frequently associated with congenital Zika syndrome.

Newborns of women infected with ZIKV during pregnancy have a 5 to 14 percent risk of congenital Zika syndrome and a 4 to 6 percent risk of ZIKA-associated microcephaly.

A study involving pregnant women from Rio de Janeiro used a broader definition for ZIKV-associated outcomes and identified adverse outcomes in 42 percent of fetuses and infants exposed to the virus.

Although ZIKV infection in any trimester of pregnancy may cause congenital Zika syndrome, the risk is greatest with infections occurring in the first trimester.

Neonatal mortality in the first week of life among infants with congenital Zika syndrome may be as high as 4 to 7 percent.

Related Zika news

Among U.S. children who were born to mothers infected with ZIKV during pregnancy and who had no identified birth defects, 9 percent had at least 1 neurodevelopmental abnormality before they reached 2 years of age.

This finding underscores the need for long-term surveillance of children born to mothers with ZIKV infection.

The full spectrum and risk of congenital Zika syndrome, therefore, remain incompletely delineated, concluded this NEJM editorial.

News published by Zika News

Our Trust Standards: Medical Advisory Committee

- Zika Virus Infection — After the Pandemic

- Zika Virus Infection in Pregnant Women in Rio de Janeiro

- Delayed childhood neurodevelopment and neurosensory alterations in the second year of life in a prospective cohort of ZIKV-expos

- WHO: Infant feeding in areas of Zika virus transmission

- CDC: Zika Virus Microcephaly & Other Birth Defects