Mosquito Saliva Quickly Spreads Diseases to People

A recent report described how a mosquito saliva component is required for virus infection.

When infected mosquitoes bite people, they inject viruses and saliva into the skin. The saliva is biologically active and helps the mosquito feed but also helps the virus to infect and replicate.

And ‘host responses to Aedes mosquito saliva is remarkably rapid, inducing peak edema and monocyte influx within minutes postexposure.’

The University of Leeds Virus-Host Interaction Team researchers announced on June 9, 2022, that the molecule sialokinin makes it easier for many viruses to pass from mosquitoes to humans.

This research suggests that blocking sialokinin may be an exciting new approach that prevents severe disease following infection with numerous distinct viruses.

Inspecting the behavior of sialokinin on skin cells from mice, the Leeds team discovered that the molecule causes blood vessels to become permeable, allowing contents to leak out into the skin – which inadvertently helps viruses to infect the host.

Research supervisor Dr. Clive McKimmie, Associate Professor in Leeds’ School of Medicine, said: “We have identified sialokinin as a key component within mosquito saliva that worsens infection in the mammalian host.

“Our research suggests that blocking sialokinin, for example, through a vaccine or a topical treatment, may be an exciting new approach that prevents severe disease following infection with numerous distinct viruses.”

These viruses include Yellow Fever, which causes serious illness in about 15% of people infected; dengue, which can develop into the potentially fatal disease dengue fever, and Zika, which caused a global medical emergency in 2016.

Lead author Dr. Daniella Lefteri added, “Our findings may also explain why some mosquitoes can spread infection to humans, while some cannot. For example, Anopheles mosquitoes cannot spread most viruses.”

“Crucially, we show that their saliva, which cannot cause leaky blood vessels and cannot enhance infection of virus in a mammalian host, does not contain sialokinin.

“Our work has increased our understanding of how mosquito-derived factors influence infection in a host’s body.”

Viruses spread by mosquitoes are known as arboviruses.

They can affect humans and other mammals, such as cattle. In humans, symptoms generally occur three to 15 days after exposure and can last three to four days. The most common symptoms are a debilitating fever and headache, but the more serious disease can occur, and some infections prove fatal.

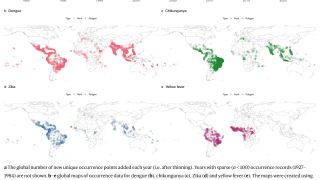

The Aedes genus of mosquito is found on all continents except Antarctica and spreads arboviruses. Species include the Asian tiger mosquito and the Yellow fever mosquito.

- Yellow fever infects people living in and visiting parts of South America and Africa. Symptoms include fever, chills, headache, backache, and muscle aches. About 15% of cases develop into serious illnesses that can be fatal.

- Dengue is contracted by people visiting or living in Asia, the Americas, or the Caribbean. According to the World Health Organisation, 5.2 million people contracted the disease in 2019. Half of the world’s population is now at risk of infection.

- Zika is found in parts of South and Central America, the Caribbean, the Pacific islands, Africa and Asia. It can harm a developing baby. In 2016, thousands of babies were born brain-damaged after their mothers became infected while pregnant.

There are currently no specific treatments or vaccines for Zika and other potentially mosquito-borne severe viruses, including Chikungunya, West Nile virus, Semliki Forest virus, and Rift Valley fever virus.

The research team says future work should focus on identifying the other factors in mosquito saliva that help viruses infect hosts and developing therapeutics to target and block them.

Dr. McKimmie said: “One way to do this would be to develop a vaccine that generates neutralizing antibodies that bind to these factors, and thereby stop them from working and helping the virus.”

This research article was published by PNAS and edited by Carolina Barillas-Mury, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD

Vax-Before-Travel published fact-checked, research-based travel vaccine news curated for mobile readership.

Our Trust Standards: Medical Advisory Committee