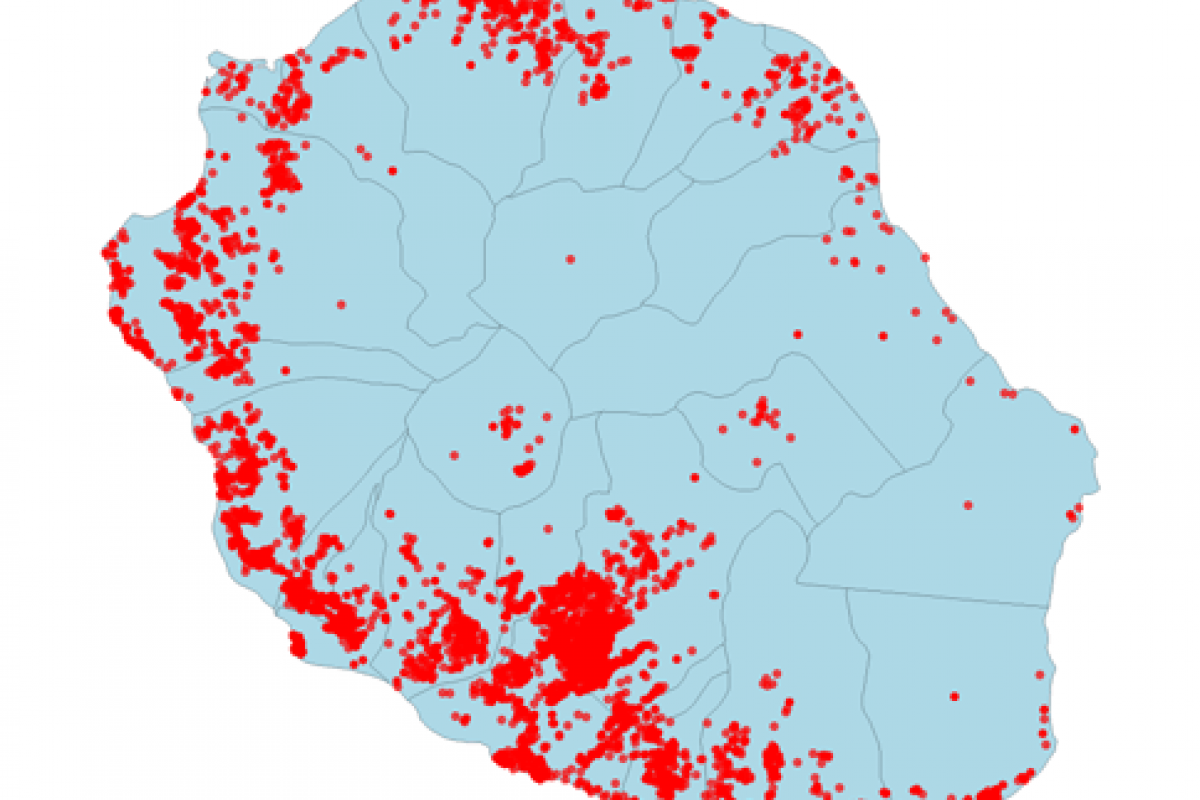

Over the past two decades, about 18 million Brazilians have been infected with one of Dengue's four viruses.

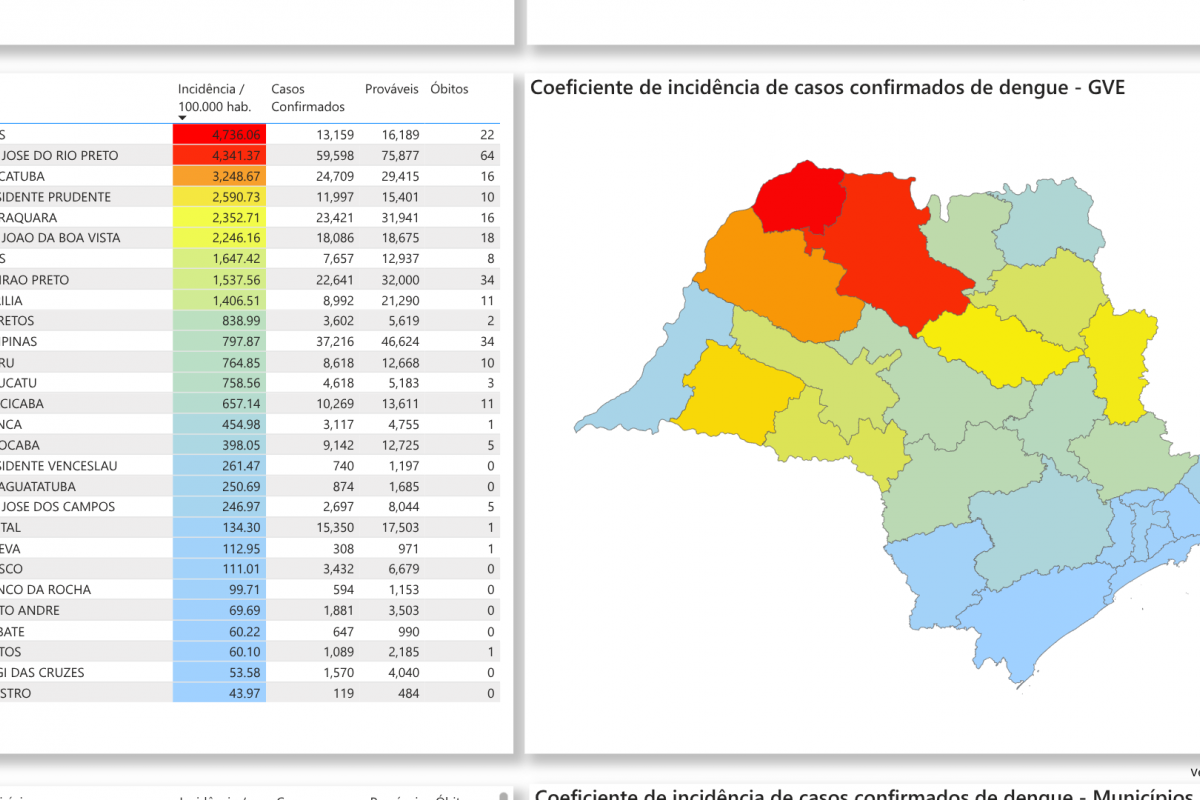

As of March 23, 2025, the Sao Paulo Ministry of Health's Dengue data dashboard indicates over 403,000 probable cases and 273 related fatalities have been reported this year.

The São José do Rio Preto region is the unfortunate leader during this Dengue outbreak, with 86 fatalities.

Throughout Brazil, one million Dengue cases and 304 fatalities have already been reported in 2025.

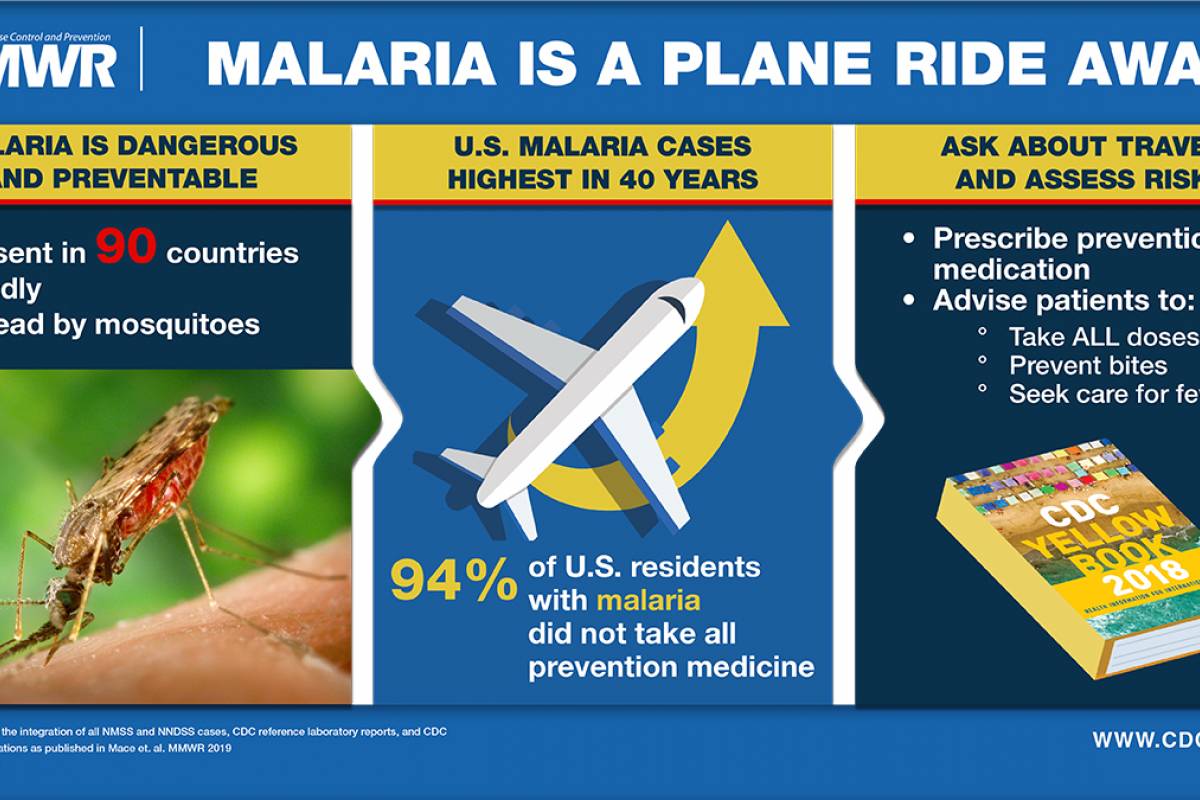

To notify international travelers of this infectious disease risk in Brazil, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently published three notices.

On March 19, 2025, the CDC reported 1,158 travel-related Dengue cases and one local case in 28 jurisdictions this year. Of these, 3% were Severe Denge cases. DENV-3 was the most (84%) common serotype identified in 2025.

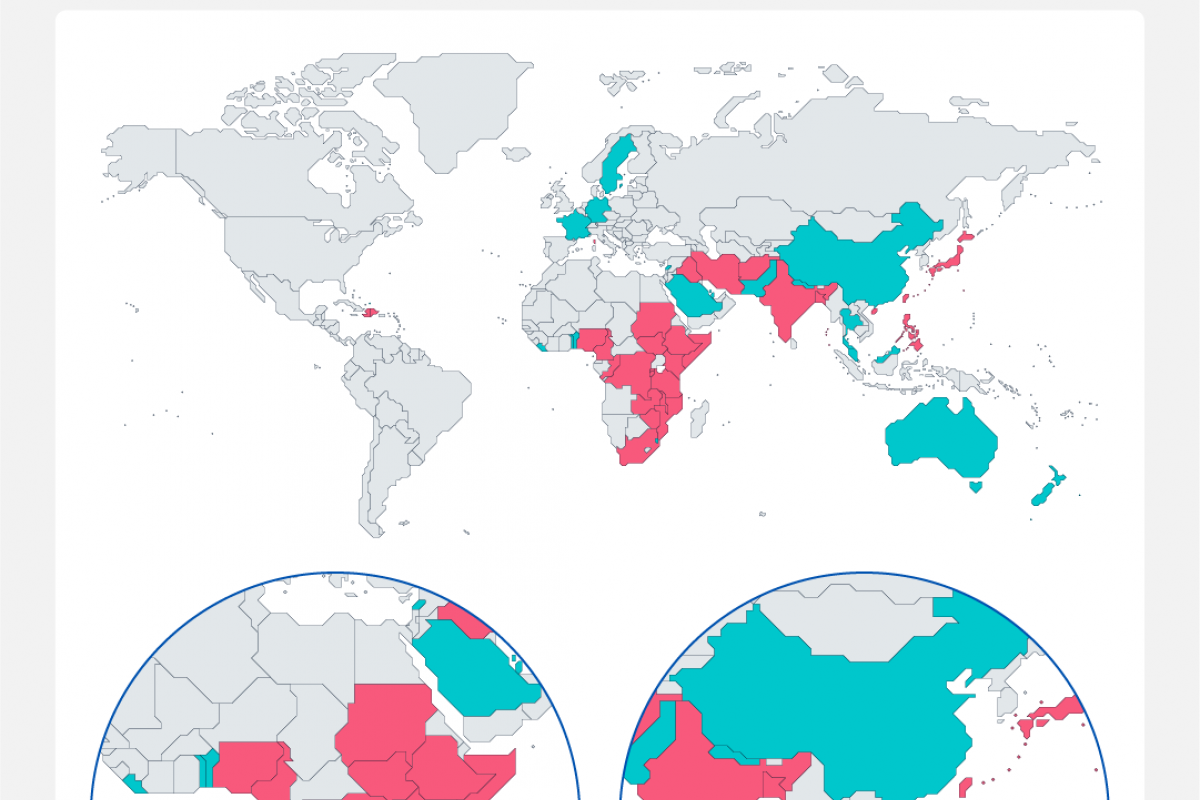

The CDC recently reissued a Global Travel Health Notice regarding Dengue outbreaks in the Region of the Americas. Transmission of Dengue remains high in the U.S. territories of Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

And on March 18, 2025, the CDC's Health Update (CDCHAN-00523) highlighted the ongoing risk of Dengue virus infections and updated testing recommendations in the United States.

As of March 23, 2025, the CDC has not issued travel advisories for U.S. cities reporting Dengue cases, such as southeast Florida. Nor does the CDC endorse Dengue vaccinations in 2025.