HIV Vaccine Proof-In-Principle Study Found Successful

An experimental vaccine developed by scientists at Scripps Research and IAVI reached an important milestone by eliciting antibodies that can neutralize a wide variety of Human Immunodeficiency (HIV) strains.

This is important news since developing an effective HIV vaccine has been a major goal of scientists ever since the virus was identified in 1983.

HIV's rapid mutation rate and other mechanisms for evading immune attacks have made it an extremely difficult target for vaccine designers over the years.

Scripps published a press release on November 18, 2019, saying ‘the tests, in rabbits, showed that these "broadly neutralizing" antibodies, or bnAbs, targeted at least 2 critical sites on the HIV virus.’

Furthermore, these ‘researchers widely assume that a vaccine must elicit bnAbs to multiple sites on HIV if it is to provide robust protection against this ever-changing virus.’

The promising results from this study appear in Immunity, suggest that researchers are one step closer to developing an effective HIV vaccine.

"It's an initial proof-of-principle, but an important one," said the study's senior author Richard Wyatt, Ph.D., a professor in the Department of Immunology and Microbiology at Scripps Research, in this press release.

“We're now working to optimize this vaccine design.”

About 38 million people are now living with HIV infection, says the UNAIDS.

Antiviral drugs can keep HIV-infected people alive and reduce their ability to transmit the virus to others, but these medications do not clear the infection and must be taken indefinitely.

Test conducted by Dr. Wyatt and his team confirms that vaccination can elicit the kinds of antibodies that are needed to provide broad protection against HIV.

These bnAbs, as vaccine experts call them, can neutralize multiple HIV strains because they bind to critical sites on the virus that do not vary much from strain to strain.

People who are infected with HIV sometimes produce bnAbs as part of their antibody response, but infrequently and usually after an infection has been long established.

The chief challenge for HIV vaccine designers has been to find ways to stimulate the immune system--in most or all individuals--into making bnAbs that hit multiple vulnerable sites on the virus, in order to protect against a high proportion of HIV strains.

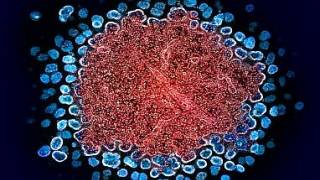

At the heart of the vaccine design by Dr. Wyatt and colleagues is a virus-mimicking protein based on HIV's "Env" protein.

Normally, multiple copies of bush-like Env proteins are spread out on the surface of each spherical HIV particle. Each Env protein contains a molecular mechanism that allows it to bind to a receptor on immune cells known as CD4, and use that receptor as a portal to break into the cell.

These researchers engineered a version of Env that models the essential structures on the real Env while being stable enough to use as a vaccine.

To present it in a way that would resemble a real HIV virus particle, they created virus-sized synthetic spheres of fat-related molecules, "liposomes," which are studded densely with the engineered Env proteins.

On a natural HIV Env protein, thickets of sugar-related molecules called glycans normally help shield the all-important CD4 binding site from immune attack. As an initial "priming" immunization, the researchers used versions of Env in which this glycan shield around the CD4 binding site had been partly removed.

"The idea was to better expose this site and thereby stimulate a broad antibody reaction to it at the start," Dr. Wyatt says.

Subsequent booster immunizations over 48 weeks used Env proteins with restored glycans, to select for antibodies that target the CD4 binding site but can also get through this shield.

The Env proteins in the booster shots also were mixes based on different strains of HIV, to generally promote antibody responses against Env structures that do not vary among these strains.

This finding is an important demonstration that vaccination against HIV if done in the right way, can achieve the goal of inducing bnAbs to multiple sites on the virus, Dr. Wyatt concluded.

The team of scientists are continuing to test and improve their vaccine strategy in small animal models and hope eventually to test it in monkeys and then humans.

The co-lead authors of the study, "Vaccination with Glycan-Modified HIV NFL Envelope Trimer-Liposomes Elicits Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies to Multiple Sites of Vulnerability," were Viktoriya Dubrovskaya, PhD, and Gabriel Ozorowski, PhD, of Scripps Research and Karen Tran, PhD, of the IAVI Neutralizing Antibody Center at Scripps Research. The laboratory of Andrew Ward, PhD, a professor in the Department of Integrative Structural and Computational Biology at Scripps Research, contributed by performing high-resolution electron microscope imaging of E70 and 1C2 bound to vaccine immunogens. Also collaborating on the project were researchers at the University of Southampton, UK, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in Maryland, the Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, and the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle.

Support for the research was provided by the National Institutes of Health (P01 AI104722, R01 AI136621, UM1 AI100663), the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation Collaboration for AIDS Vaccine Discovery (OPP1115782, OPP1084519) and IAVI. No conflicts of interest were disclosed.

HIV Vaccine news published by Precision Vaccinations

Our Trust Standards: Medical Advisory Committee