A Triumph for Injectable PrEP

A presentation on the HPTN 084 study delivered on January 27, 2021, confirmed the results announced when the trial was stopped early in November 2020 but added new details.

This presentation focused on women randomly allocated to receive injectable PrEP (every eight weeks) or oral PrEP (every day).

The study used a 'double-dummy' design, meaning that half the participants got active injectable cabotegravir and inactive placebo pills; the other half got inactive placebo injections and active tenofovir/emtricitabine pills.

Whereas there were 36 infections in women assigned the active PrEP pills, there were only four in women given the active injections. Two of the four had not had any injections at the time of infection, one had been injected four months previously, and one woman did acquire HIV despite following the injection schedule.

In the absence of these prevention options in the study communities, HIV incidence is approximately 3.5% a year.

The study’s oral PrEP arm was 1.9%, and in the injectable PrEP arm, it was 0.2%.

The researchers believe that lower adherence to the pills likely explains these results.

At week 4, only 60% of women in the oral PrEP arm had blood levels of tenofovir consistent with daily dosing, which declined to 34% by week 57.

In contrast, women attended 93% of their injection visits, a figure that only declined slightly over time.

In terms of side effects, there were more injection site reactions in women receiving the active injections (32%) than in those receiving placebo injections (9%). Still, these were mostly minor and did not lead to anyone withdrawing from the study.

Delany-Moretlwe signaled two essential simplifications to how injectable cabotegravir is likely to be implemented.

In the study, women took cabotegravir pills (or placebo pills) for five weeks before starting the injections. The rationale was to ensure that cabotegravir is well-tolerated since the injectable cannot be removed from the body if it causes problems.

However, the evidence from this and other studies is that such side effects are rare, so the oral ‘lead in’ may not be necessary.

The other suggested simplification concerns the ‘long tail’.

This refers to the persistence of low levels of cabotegravir in the body for many months after a person’s last injection. The individual will be vulnerable to HIV unless they start or continue another method of HIV prevention, such as oral PrEP.

The ‘long tail’ means a long period during which, if they caught HIV, they could develop drug resistance. Drug resistance only arises in situations like this when there is some drug in the body but not enough to entirely suppress an infection.

To deal with this concern, study participants who stopped receiving injectable cabotegravir were offered a year-long course of oral PrEP. There are questions about how practicable this will be in real-world settings.

"Injections offer a real alternative and fit in with women’s already existing sexual and reproductive health practices.”

Delany-Moretlwe argued that healthcare providers' vital thing to do would be to understand why the person is discontinuing. If they want to stop because they no longer feel at risk of HIV infection, they may not acquire HIV or develop drug resistance. If the injections are not right for them, the provider should explore alternative HIV prevention options.

However, there was some pushback from conference delegates on this point. Stopping will not always be a conscious choice, and many people will simply be lost to follow-up. An increasing prevalence of strains of HIV that are resistant to cabotegravir would be a risk to HIV treatment programs that are now based on dolutegravir (a drug from the same class).

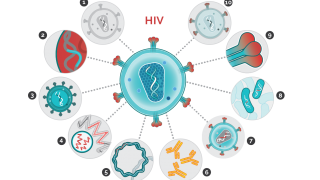

Nonetheless, the general mood is of excitement about the increasing range of HIV prevention options, including oral tenofovir/emtricitabine, the dapivirine vaginal ring (recommended in World Health Organization guidelines), and injectable cabotegravir.

The injection will be submitted for approval by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2021 and then to other regulatory agencies.

Delany-Moretlwe S et al. Long-acting injectable cabotegravir is safe and effective in preventing HIV infection in cisgender women: interim results from HPTN 084. HIV Research for Prevention (HIVR4P) virtual conference, abstract HY01.02, 2021.

PrecisionVaccinations publishes research-based news.

Our Trust Standards: Medical Advisory Committee