Are 3 Measles Vaccinations Needed?

A new commentary published in The Lancet discusses the long-term immunity related to early vaccinations intended to protect infants from the measles virus.

This editorial published on September 20, 2019, indicates a 3-dose measles vaccine schedule may be needed in ‘outbreak zones.’

But, this disease prevention approach would be difficult and costly to implement, as the current 2-dose vaccination schedule already sees poor adherence.

This discussion is important since ‘unvaccinated young children are at highest risk of measles and its complications, including death,’ says the World Health Organization (WHO).

Excerpts from this Lancet article are inserted below:

The optimal age for measles-containing vaccine (MCV) administration depends on various factors, mainly the duration of the protection induced by transplacentally acquired maternal immunity, the maturity of the infant's immune system, and the average age of measles infection in different geographical areas.

Initially, experts thought that if an area had a high risk of measles outbreaks, a first dose of MCV at 9 months of age could be enough to protect most infants, as those younger than 9 months could avoid infection through transplacentally acquired immunity.

Subsequently, it was shown that this supposition was partly wrong, as many measles cases, sometimes very severe, were diagnosed in infants younger than 6 months.

This finding was attributed to a shorter-than-expected duration (9–12 months) of passive maternal immunity, evidenced in both infants born from vaccinated mothers and those born from mothers with naturally acquired immunity.

It was shown that vaccination stimulated the immune system less than natural infection, and infants born from vaccinated mothers had lower specific antibody titers with more rapidly waning protection than infants born from naturally infected mothers.

Nevertheless, with the introduction of MCV administration, the circulation of the measles virus progressively declined and, without this natural booster, even previously naturally infected mothers transferred reduced antibody concentrations to their fetuses.

To address the problem of measles infection in young infants, an early MCV dose before 9 months of age was suggested.

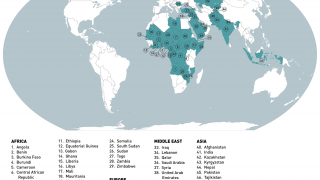

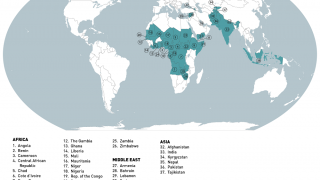

Infants living in or traveling to countries with frequent measles outbreaks, or considered at risk because of HIV exposure or infection, and refugees or people living in conflict zones were the target populations.

However, because of the risk that an early MCV dose could lead to poor short-term and long-term protection, this dose was considered only supplemental. Infants vaccinated before 9 months of age had to receive the usual two doses at scheduled times to achieve long-term protection.

Unfortunately, the real effect of an early MCV dose has not been definitively established. Attempts to fill this gap have been made by Laura Nic Lochlainn and colleagues with two systematic reviews and meta-analyses published in The Lancet Infectious Diseases.

The results indicate that MCV administration before 9 months of age is safe and immunogenic.

Moreover, early immunization did not blunt the immune response to subsequent MCV doses.

Consequently, the authors concluded that the administration of MCV to infants younger than 9 months can be an effective solution to reduce measles-related morbidity and mortality in a substantial proportion of infants at risk.

However, the results of Nic Lochlainn and colleagues strongly suggest that MCV administration before 9 months of age must only be considered as an emergency solution to contain or prevent outbreaks and cannot replace either scheduled dose.

Compared with infants administered MCV at 9 months of age or later, seroconversion and antibody concentrations in those vaccinated before 9 months of age were significantly reduced.

Vaccine efficacy was 51% versus 83%, highlighting that a substantial proportion of infants younger than 9 months remained susceptible to measles and that only further doses could ensure that all infants were protected.

Moreover, analysis of the immunogenicity and efficacy of further doses, despite showing that MCV efficacy and cell-mediated responses to a second and a third dose were independent of the age of the first dose, suggests that an early dose might decrease long-term protection because further doses were associated with reduced antibody titers and avidity.

Further studies are needed to solve the problem of reduced long-term immunity after early MCV administration.

>>> Check your Measles Immunity <<<

In the meantime, WHO's recommendations on vaccination must be followed.

The need for a three-dose regimen presents organizational and economic difficulties, particularly in low-income countries. Only countries with well-established immunization can rely on routine services to deliver the second and third doses.

Together with additional expenses, which are difficult to sustain in low-income countries, the uptake of routine vaccination after receipt of an early dose can be suboptimal.

Although data on vaccination uptake in developing countries are insufficient, a Canadian study showed that approximately 20% of early-vaccinated children, mainly in low-income families, did not receive further doses at the appropriate time.

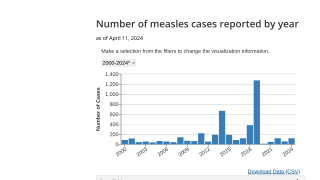

The most important obstacle to measles elimination by 2020 in five of the six WHO-targeted regions is the poor vaccination coverage in countries where measles had been nearly eradicated.

Coverage with two doses at recommended ages was less than 95% in 96·5% of European countries, and the prevalence of measles protection according to antibody titers was significantly lower than the herd immunity threshold in these countries (76% vs 95%).

Similar suboptimal vaccination coverage was seen in several other countries outside Europe, including the USA.

Circulation of measles virus among adolescents and adults predominantly affects unvaccinated young infants. Only total compliance to recommendations can solve the problem of poor vaccination coverage.

Previously, the WHO reported in 2017, about 85% of the world's children received 1 dose of measles vaccine by their first birthday through routine health services. This is an increase from 72% in 2000.

In 2017, 67% of children received the second dose of the measles vaccine.

Of the estimated 20.8 million infants not vaccinated with at least one dose of measles vaccine through routine immunization in 2017, about 8.1 million were in 3 countries: India, Nigeria, and Pakistan.

The most recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommendations for measles vaccination were published in 2013 and can be found here.

The CDC says the ‘MMR vaccine can be given to children as young as 6 months of age who are at high-risk of exposure, such as during international travel or a community outbreak.’

‘However, measles vaccine doses given before 12 months of age cannot be counted toward the 2-dose series for MMR vaccination.’

These authors did not declare any competing interests.

Published by Precision Vaccinations

Our Trust Standards: Medical Advisory Committee

- Early vaccination: a provisional measure to prevent measles in infants

- mmunogenicity, effectiveness, and safety of measles vaccination in infants younger than 9 months: a systematic review and meta

- Effect of measles vaccination in infants younger than 9 months on the immune response to subsequent measles vaccine doses

- WHO: Measles

- Ask the Experts: Measles, Mumps and Rubella