Mexico’s Zika Virus Reporting Questioned

New research found evidence that the Zika virus epidemic in Mexico reversed the declining trend of infant deaths from microcephaly in 2016-2017.

Additionally, this study published by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) on July 6, 2019, found that the number of deaths from microcephaly associated with Zika virus was 50 percent greater than that reported by Mexico’s Zika disease surveillance system.

Furthermore, this study reported the Mexican National Institute of Statistics and Geography data between 2016–2017 represents the Congenital Zika Syndrome (CZS) case-fatality rate was 22 percent.

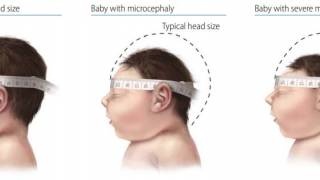

These deaths were attributable to a CZS condition called Microcephaly.

Microcephaly is a congenital malformation resulting in smaller than normal head size and has also been associated with other birth defects and neurologic conditions in children.

Based on the attributable risk, these researchers expected about 17 infant deaths from microcephaly, "indicating that 50% more infants died of microcephaly caused by CZS than were reported."

Zika Symptoms

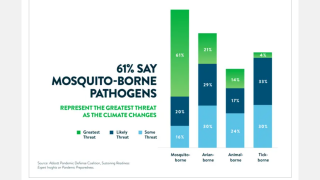

The Zika virus is spread mostly by the bite of an infected Aedes species mosquito (Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus). These mosquitoes bite during the day and night.

Many people infected with Zika virus won’t have symptoms or will only have mild symptoms. People usually don’t get sick enough to go to the hospital, and they very rarely die of Zika.

For this reason, many people might not realize they have been infected. Symptoms of Zika are similar to other viruses spread through mosquito bites, like dengue and chikungunya.

Currently, there is no preventive vaccine or medicine to treat a Zika infection, says the CDC.

This study estimated infant mortality rates by using the number of registered live births per year for all of Mexico. Because the Zika virus epidemic in Mexico started in November 2015, the exposure period of interest was 2016–2017.

A permutation test was used to identify the most parsimonious results. Infant deaths possibly resulting from the Zika virus epidemic were estimated by using the attributable risk and compared with the number of fatal CZS cases reported by the existing CZS surveillance system.

From 1998 through 2017, a total of 467 infants died of microcephaly in Mexico. Joinpoint regression identified an overall significant decrease of 6.80% APC (95% CI –11.9% to −1.4%) for 2007–2015 and a statistically significant increase of 27.25% APC for 2016–2017 (95% CI 3.0% to 57.2%).

On the basis of the results of the trend analysis and the documentation of the first Zika virus outbreak in Mexico during November of 2015, we selected the period 2007–2015 as the baseline.

During the epidemic period (2016–2017), the rate of infant deaths from microcephaly was 1.17 deaths/100,000 live births; during the preceding 4 years (2007–2015), the rate was 0.80 deaths/100,000 live births. Thus, the rate ratio was 1.5 (95% CI 1.1–2.0).

The attributable Zika risk was found to be 31.7 percent.

Zika news

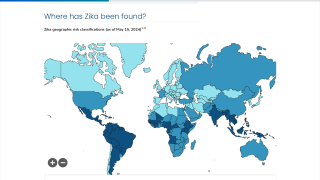

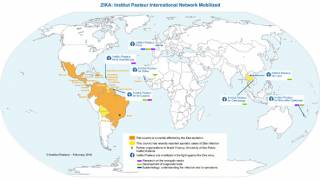

- Zika Remains a Worldwide Health Risk to Pregnant Women

- Zika Exposure While Pregnant Associated with Microcephaly

- US Government Makes 2nd Zika Investment

- New Legislation May Protect the USA From Zika

This study’s assessment is not without limitations.

First, it was limited to fatal CZS and relies on the International Classification of Diseases coding. In addition, the accuracy of microcephaly as the underlying cause of death is unknown; microcephaly could have been present among other conditions mentioned in death records but not selected as the underlying cause of death.

Several factors may lead to incomplete reporting of the Zika virus epidemic and CZS.

Had primary infection with Zika virus during pregnancy not resulted in CZS, Zika virus would have gone mostly unnoticed, as do many other arboviral infections, such as dengue and chikungunya.

And, reporting of communicable diseases in Mexico, as in other countries, is far from complete.

To improve the Zika virus and CZS surveillance in Mexico, resources could be more efficiently used.

Zika-endemic areas could be targeted, using active surveillance to monitor the occurrence of microcephaly at birth and flagging neonates born with gestational age and gender-specific head circumference <2 SDs of the reference.

And, the Mexican surveillance system could use sentinel sites selected according to the existing risk stratification strategies used for dengue, which could enable extrapolation of the data to the rest of the country.

Previously, the Public Health Agency of Canada issued advice for travelers, recommending that Canadians practice special health precautions while visiting Zika affected countries.

Specifically, Canada says ‘pregnant women and those considering becoming pregnant should avoid travel to Mexico.

The lead researcher was Victor Cardenas, M.D., MPH, Ph.D., FACE is an associate professor of epidemiology at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. He is currently conducting research on the role of environmental factors such as Zika virus and electronic cigarettes on pregnancy outcomes.

Other study authors were Angel Jose Paternina-Caicedo, and Ernesto Benito Salvatierra. Affiliations include the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, Arkansas, USA (V.M. Cardenas); Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogota, Colombia (A.J. Paternina-Caicedo); Unidad San Cristóbal, Chiapas, Mexico (E.B. Salvatierra).

Our Trust Standards: Medical Advisory Committee