19 Massachusetts Communities at Critical Risk for Eastern Equine Encephalitis Virus

The Massachusetts Department of Public Health (DPH) today announced that laboratory testing confirmed the 2nd case of Eastern Equine Encephalitis virus infection.

In total, there are 19 Massachusetts communities now at critical risk, 18 at high risk, and 24 at moderate risk for the Eastern Equine Encephalitis virus (EEEV), as determined by DPH as of August 16, 2019.

To protect Massachusetts residents, the DPH and the Department of Agricultural Resources conducted aerial spraying in specific areas of Bristol and Plymouth counties to reduce the mosquito population and public health risk.

A 2nd round of aerial spraying in Massachusetts is planned for late August.

This is unfortunate news since approximately 30 percent of all people with EEEV die from the disease.

Furthermore, there is not a human vaccine against EEEV infection or specific antiviral treatment available, says the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Patients with suspected EEEV should be evaluated by a healthcare provider, appropriate serologic diagnostic tests ordered, and supportive treatment provided.

The EEEV occurs sporadically in Massachusetts with the most recent outbreaks occurring from 2004-2006 and 2010-2012. There were 22 human cases of EEEV infection during those 2 outbreak periods, with 14 cases reported in Bristol and Plymouth Counties.

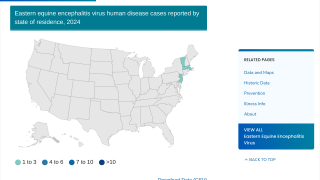

Throughout the USA, there were 6 human EEEV cases confirmed by the CDC in 2018. EEEV transmission is most common in and around freshwater hardwood swamps in the Atlantic and Gulf Coast states, led by the states of Florida and Massachusetts.

Eastern equine encephalitis virus is an arbovirus belonging in the genus Alphavirus, family Togaviridae. Western and Venezuelan are 2 other types, says the CDC.

EEEV infection can result in 2 types of illness, systemic or encephalitic, which involves swelling of the brain. The incubation period for EEEV disease ranges from 4 to 10 days.

Systemic infection has an abrupt onset and is characterized by chills, fever, malaise, arthralgia, and myalgia. Signs and symptoms in encephalitic patients are fever, headache, irritability, restlessness, drowsiness, anorexia, vomiting, diarrhea, cyanosis, convulsions, and coma.

The illness lasts 1 to 2 weeks, and recovery is complete when there is no central nervous system involvement.

In infants, the encephalitic form is characterized by abrupt onset; in older children and adults, encephalitis is manifested after a few days of systemic illness.

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) findings include neutrophil-predominant pleocytosis and elevated protein levels; glucose levels are normal. Brain lesions are typical of encephalomyelitis and include neuronal destruction and vasculitis, which is perivascular and parenchymous at the cortex, midbrain, and brain stem.

Of those who recover, many are left with disabling and progressive mental and physical sequelae, which can range from minimal brain dysfunction to severe intellectual impairment, personality disorders, seizures, paralysis, and cranial nerve dysfunction.

Many patients with severe sequelae die within a few years.

EEEV is difficult to isolate from clinical samples; almost all isolates (and positive PCR results) have come from brain tissue or CSF. Serologic testing remains the primary method for diagnosing EEEV infection.

A May 2019 study reported there is a strategy to develop a EEEV vaccine candidate.

These researchers designed a trivalent vaccine to simultaneously fend off Eastern, Western, and Venezuelan equine encephalitis viruses.

This study generated a trivalent EEEV vaccine composed of virus-like particles (VLPs). In this study, nonhuman primates were immunized with trivalent VLPs were completely protected against aerosol challenge by each of the EEEVs.

These researchers said ‘Because they are replication-incompetent, these trivalent VLPs represent a potentially safe and effective vaccine that can protect against diverse encephalitis viruses.’

All Massachusetts residents have an important role to play in protecting themselves and their loved ones from illnesses caused by mosquitoes.

- Apply Insect Repellent when Outdoors. Use a repellent with an EPA-registered ingredient (DEET (N, N-diethyl-m-toluamide), permethrin, picaridin (KBR 3023), oil of lemon eucalyptus [p-methane 3, 8-diol (PMD)] or IR3535) according to the instructions on the product label. DEET products should not be used on infants under two months of age and should be used in concentrations of 30% or less on older children. Oil of lemon eucalyptus should not be used on children under three years of age.

- Be Aware of Peak Mosquito Hours. The hours from dusk to dawn are peak biting times for many mosquitoes. Consider rescheduling outdoor activities that occur during evening or early morning in areas of high risk.

- Clothing Can Help Reduce Mosquito Bites. Wearing long-sleeves, long pants and socks when outdoors will help keep mosquitoes away from your skin.

- Drain Standing Water. Mosquitoes lay their eggs in standing water. Limit the number of places around your home for mosquitoes to breed by either draining or discarding items that hold water. Check rain gutters and drains. Empty any unused flowerpots and wading pools, and change the water in birdbaths frequently.

- Install or Repair Screens. Keep mosquitoes outside by having tightly-fitting screens on all of your windows and doors.

For the most up-to-date information available on spraying locations, visit the Massachusetts Department of Agricultural Resources Aerial Spraying Map.

For other updates, Q&As, and downloadable fact sheets in multiple languages visit the DPH webpage.

Our Trust Standards: Medical Advisory Committee