Dengue Hotspots Can Predict Future Chikungunya and Zika Outbreaks

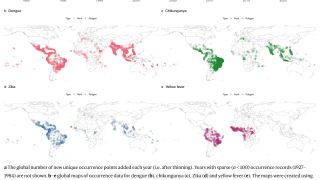

It appears knowing where dengue fever virus has previously had an outbreak can mathematically predict where future chikungunya (CHIKV) and Zika virus (ZIKV) outbreaks will occur.

An international team of researchers analyzed geo-coded reports from the city of Merida, Mexico, with the goal of assessing the utility of historical dengue (DENV) data to infer the introduction and propagation of other infectious diseases.

Since DENV, CHIKV, and ZIKV are all primarily transmitted by Ae. aegypti mosquitoes, these researchers early assumption was that ZIKV would follow the path of the other two viruses in the Americas.

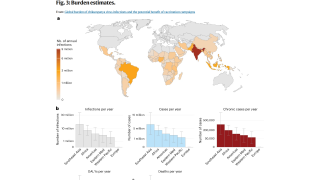

This study found about 42 percent of the 40,028 dengue cases reported during 2008–2015 were clustered in just 27 percent of the city.

Additionally, these city blocks were where the first CHIKV and ZIKV cases were reported in 2015 and 2016.

These DENV clustering areas reported 35.6 percent of all reported CHIKV cases and 66.9 percent of all ZIKV cases.

Gonzalo Vazquez-Prokopec, a disease ecologist in Emory’s Department of Environmental Sciences and lead author of the study, said: “The results open a window for public health officials to do targeted, proactive interventions for emerging Aedes-borne diseases.”

Mosquito control efforts generally involve outdoor spraying which is particularly ineffective for the Aedes aegypti mosquito.

“This mosquito is highly adapted to urban environments,” Vazquez-Prokopec said.

“You tend to see transmission go down right after large numbers of a population are infected with these Aedes-borne viruses, leading to herd immunity,” Vazquez-Prokopec says. “But these viruses do not disappear. They keep circulating and can reappear later.”

Since vaccines are not readily available for these infectious diseases, mosquito control is the best, preventive tactic.

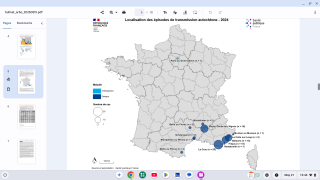

On the island of Cuba, health officials have deployed a very aggressive, localized approach to eliminating disease-carrying mosquitoes.

Cuba deploys 15,000 workers who “visit every house in Cuba” to look for mosquitoes and kill them, said Nilda Roca Menendez, director of health and epidemiology for Havana.

“In Havana, each mosquito-control worker is responsible for 300 households and is expected to visit 20 each day, checking for mosquitoes, larvae, and standing water that could become breeding grounds.”

“If a case of Zika, dengue, or chikungunya virus is diagnosed, or mosquitoes or larvae are found, every home within 100 meters will be checked more intensely,” Menendez said.

These researchers did not disclose any conflicts of interest. Research funding was provided by the National Science Foundation (DEB/EEID award: 1640698), the Office of Infectious Disease, Bureau for Global Health, U.S. Agency for International Development, under the terms of an Interagency Agreement with the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC: OADS BAA 2016-N-17844), and by partial support from the National Institutes of Health through the MIDAS research network (U54 GM111274) and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and IDRC (Preventing Zika disease with novel vector control approaches, Project 108412). 'SANOFI Pasteur financed the cohort study (DNG25) for which HGD and NPR were PIs.

Our Trust Standards: Medical Advisory Committee