Booster Rotavirus Vaccination In Infants May Not Be Needed

According to a new study, giving children an additional dose of rotavirus vaccine when they are 9-months old would provide only a modest improvement in the vaccine's effectiveness.

In response to concerns about the rotavirus vaccines' effectiveness in low-income countries, a team of researchers led by Associate Professor Virginia Pitzer of the Yale School of Public Health and Professor Nigel Cunliffe of the University of Liverpool published on August 14, 2019, a detailed mathematical analysis of rotavirus vaccinations and diarrhea cases reported in southeastern Africa.

With access to 12 years of pre-vaccination and 5 years of post-vaccination data, the analysis predicted that 1 extra dose of rotavirus vaccine at 9-months of age would provide only a modest 5-16 percent reduction in overall case incidence over the first 3 years.

"Our analysis revealed that lower vaccine effectiveness during the 2nd year of life is not necessarily indicative of waning rotavirus vaccine protection," said Pitzer, the study's lead author and an expert in the epidemiology of microbial diseases in the Yale School of Public Health's public health modeling unit.

This study documented a high-rate of rotavirus transmission.

As a result, vaccination provides only partial protection and tends to delay cases among vaccinated infants to the second year of life, according to the study.

A poor immune response to oral vaccination due to other causes of inflammation in the gut and interference from other vaccines, such as those for polio, may also impact vaccine effectiveness.

"Strategies to enhance the immune response to initial vaccination, including the use of next-generation vaccines that are currently in development, may lead to enhanced and more durable vaccine impact," said Cunliffe, an expert in gastrointestinal infections at the University of Liverpool's Centre for Global Vaccine Research.

Other study contributors were: Aisleen Bennett, Naor Bar-Zeev and Khuzwayo Jere from the Malawi-Liverpool-Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Programme at the University of Malawi; Benjamin Lopman from the Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University; Joseph Lewnard from the University of California, Berkeley School of Public Health; and Umesh Parashar from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

This research was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (R01AI112970), a Wellcome Trust Programme Grant (091909/Z/10/Z), and two Wellcome Trust fellowships (102466/Z/13/A) and (201945/Z/16/Z).

Rotavirus is a leading cause of morbidity and death from diarrhea in children worldwide, says the World Health Organization (WHO).

Although the recent introduction of rotavirus vaccines has had a substantial impact on the incidence of rotavirus-associated gastroenteritis (RVGE) in high- and middle-income countries, the impact of vaccination in low-income countries is not as well defined.

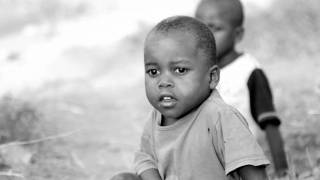

The vast majority of deaths due to rotavirus occur in low-income countries in Asia and Africa, but estimates of vaccine efficacy are lower in these settings.

Whereas vaccine efficacy was 85 to 99% in clinical trials conducted in high-income countries, efficacy was 39 to 67% in trials conducted in low-income countries for all currently available oral rotavirus vaccines.

Nevertheless, the preventable burden of disease in low-income settings is potentially much greater.

Two key questions regarding the long-term impact of rotavirus vaccines are:

- whether the direct protection conferred by rotavirus vaccination is reduced in low-income countries due to a poorer initial immune response or waning of vaccine-induced immunity

- whether vaccination will confer sustained indirect (herd) protection similar to that observed in high-income countries.

Our Trust Standards: Medical Advisory Committee