Dengue Vaccine Under Review in the Philippines

The Philippines has suspended its large-scale dengue vaccination effort amid the surprising results of a new study conducted by the vaccine's manufacturer.

A spokesman for Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte announced that the Department of Justice would launch an investigation into the approval process of Dengvaxia.

Why?

On November 29, 2017, pharmaceutical firm Sanofi Pasteur published 6 years of clinical trial data showing that its dengue vaccine, Dengvaxia, could have unintended, negative consequences in patients who had never been infected with dengue before.

But, why has Dengvaxia abruptly become so dangerous?

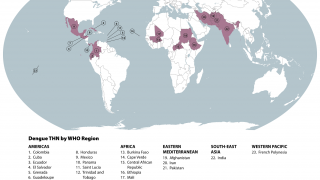

In 2009, the World Health Organization (WHO) revised the classification guidelines for severe dengue to improve clinical management of dengue patients and to capture other complications.

According to WHO, there are four "distinct, but closely related" strains of the virus that causes dengue. Once a person has an infection of one of the strains, they cannot become infected with that strain again.

But, when someone is infected with a different virus strain, the more likely subsequent infections produce "severe dengue."

"The new analysis confirmed that Dengvaxia provides persistent benefit against dengue fever in those who had a prior infection," Sanofi said in a statement.

A new study appears to answer some of these questions.

In this study, researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, studied the relationship between pre-existing anti-DENV binding antibodies (DENV-Abs). and dengue disease severity.

"If a child developed dengue, we could go back to the banked antibody samples and say, 'OK, is there something about the children's antibody levels that are different than that of the healthy kids?” says Dr. Eva Harris, an infectious disease researcher at the University of California, who led the study.

These researchers expected the presence of dengue antibodies in the child's blood would protect them from new dengue infections.

That's what antibodies are supposed to do.

But, with severe cases of dengue, the exact opposite turns out to be true, Dr. Harris and her research team report.

The antibodies actually backfire.

Inside the antibody "danger zone," children were reported in this study to be more than 7x more likely to develop severe dengue cases when compared to children who have never been infected with dengue.

More than 730,000 people in the Philippines have been vaccinated with Dengvaxia since April 2016, based upon the WHO first recommendations.

In July 2016, the WHO published a paper that cautioned, "Vaccination may be ineffective or may theoretically even increase the future risk of (hospitalization) or severe dengue illness in those who are (uninfected) at the time of first vaccination."

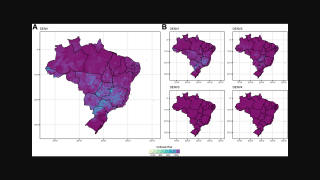

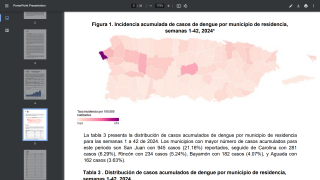

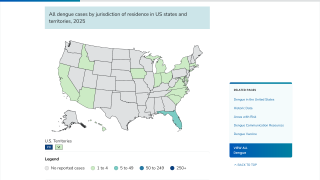

The WHO estimates roughly half of the world's population is now at risk of contracting the dengue virus and that 390 million people are infected every year.

Dengue is a viral infection transmitted by the Aedes aegypti mosquito.

According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, anyone suspected to have contracted dengue can take pain relievers with acetaminophen.

But, people should avoid taking medications containing ibuprofen or aspirin.

The WHO and Sanofi have issued a "label update" for Dengvaxia to recommend that people who have never been infected with any strain of dengue not be vaccinated.

The Sanofi label proposal will be reviewed by national regulatory agencies in each of the countries where the vaccine is registered or under registration.

Our Trust Standards: Medical Advisory Committee